Blackcaps are not an uncommon sight in Britain during the winter months nowadays. We have a ‘healthy’ wintering population of around 3,000 individuals which compares with a summer population estimate of 932,000 pairs (Birdlife International, 2004). Numbers wintering in the UK have increased considerably since the 1960s and it would seem likely that the above number is an old and conservative estimate so if anyone has an up-to-date figure I would be pleased to receive it.

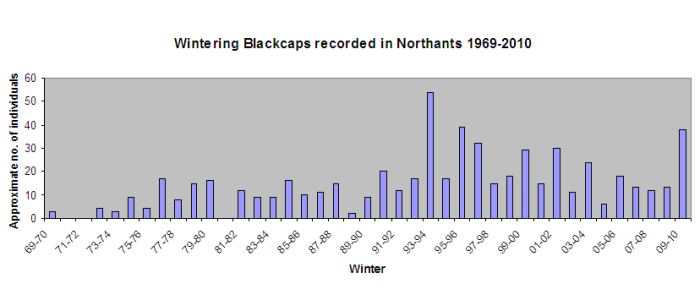

Numbers wintering in Northants appear to have risen and averaged higher since the early 1990s, although this may reflect better observer coverage and communication.

Ringing data have established that UK winterers are from a breeding population in central Europe and, while most Blackcaps from this area head south-west in autumn to winter in Spain and northern Africa, some head north-west to the UK. The driver for this is not clear but milder winters and an abundance of ‘artificial’ food (i.e. winter bird feed provided by man) have been cited as the likely reasons. The latter of the two factors appears to be the subject of debate as many observations on wintering Blackcaps point to their feeding primarily on natural food sources such as berries and insect larvae when these are available.

Dave Warner’s excellent portrait of a male in his Northampton garden last weekend illustrates this point perfectly with the principal choice of food, Dave suggests, being an abundant supply of crab apples. That said, it seems logical to assume that ‘artificial’ food may at least act as a regular supplement or backup in the absence of natural foods, thus helping maintain the wintering population.

What is clear, however, is that our wintering Blackcaps are very different from those which breed here in summer. Having a shorter distance to fly to their breeding area in spring means they arrive back before the Spanish winterers and therefore only have each other to mate with, effectively becoming reproductively isolated from the Spanish birds. So now there are morphological differences emerging. This population, in the space of little more than 50 years, has produced birds with rounder wings (as they don’t need to migrate so far) narrower and longer bills (supposedly for taking advantage of ‘artificial’ foods) and browner mantles and bills. A kind of ‘catalytic evolution.’ How far will it go? Full speciation?

So next time you come across a Blackcap in Britain in winter it’s worth remembering that it’s not just any Blackcap, it’s likely to be a breakaway Blackcap – an activist, a rebel, a pioneer and, although a potential champion of speciation, it may only ever become genetically distinct to a racial level, so don’t hold your breath for an ‘armchair tick’ any time soon …

For a more detailed look at this unfolding phenomenon see here and here.

Discover more from Northants birds

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Interesting post Mike, especially for someone who has publicly debated evolution with a creationist! See my post from a couple of months ago: http://jeffollerton.wordpress.com/2012/10/22/wrestling-the-oiled-serpent/

Your point about observer coverage and communication is well made; this is a real issue for all long term monitoring of biodiversity.

The first link at the bottom is broken by the way.

All the best,

Jeff

Hi Jeff, thanks for your comments. I will fix the link! I read your very interesting post regarding the evolutionary debate and I fully understand how this sort of debate be draining. Unfortunately, those without open minds will never see your (reasoned) side of the debate.

Hi Mike,

The first link to me back to this post, was it supposed to? The second one worked fine. Great post learnt something new today, I’ve never noticed the difference.

Sorry that should’ve read “the first link took me back to this post”…I will learn to type one day.

Thanks, Doug. It’s an interesting topic, I think.

Interesting reading, Since the recent colder weather I have a male blackcap feeding on the sunflower hearts in my garden here in Herts.

Glad you found it interesting. A few winters back I had three visiting my garden but I haven’t seen a wintering Blackcap since then.

Very interesting post Mike.

I have had overwintering Blackcaps here in Suffolk for about the last fifteen years. They spend their time in a mountain of ivy and eat large numbers of the berries, the rest of the time seems to be spent foraging for insects. I have never seen them on my feeders. In the spring there are always a pair or two breeding here. In 2010, there was a singing male from early February. I don’t know whether he left for Europe or stayed, as there was no period without a singing male.

This is the male, his song sounds, to me, the same as any of the summer visitors. Could this evolve quickly too? http://marksbirdsong.unblog.fr/2010/02/25/14/

The short answer is I don’t know. The question of song (and calls) being different had indeed occurred to me but I can’t find any references to their being different or if any investigation has been carried out along these lines. It would be interesting to compare sonograms of individuals from both populations.

A thought provoking read, thanks Mike. A pair arrived in my garden today, maybe the same pair as earlier in the year. They’re exhibiting the same behaviour with the female readily coming to the feeders & even hanging upside down on the suet while the male stays further away.

I heard the female making a strange, drawn out squeaking sound last winter when the male was in the vicinity. It was slightly slower and quieter than the call of a Gray Catbird, I had never heard the call before and I can’t find it on xeno-canto. I await full speciation, though I don’t think it will happen in my lifetime!

Thanks for this, Dave. I would like to think that, at the rate these things seem to be ‘evolving’, we may at lease see a new subspecies recognised in our lifetime!

Some years ago, I imported big bunches of mistletoe into my garden near Derby around the end of the year hoping something might eat the berries. Mistletoe is a rare plant this far north but one garden apple tree a few miles away was festooned with it and the owner allowed me to take bunches at will.

One winter in early January a female blackcap arrived and started to eat the berries, deftly separately the white flesh from the gluey seed. She ate many berries such that I had to keep collecting new bunches! She varied her diet only (as far as I could see) by eating apples I had cut in half and nailed to a nearby bird table (to stop blackbirds knocking them off). She never went near the fat or seed/peanut feeders. She stayed until late March but didn’t return the following year.

A few years later I noticed a small mistletoe plant growing on a Cotoneaster close to the bird table. ..clearly as a result of the blackcap’s efforts.

Hope of some interest.

Nick

Thanks, Nick. My own research leads me to believe that wintering Blackcaps will feed on more natural food, when available, in preference to artificial food provided by humans, which ties in well with your observations.